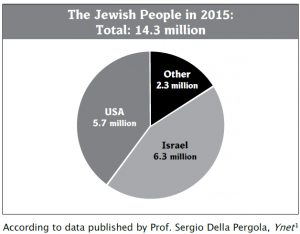

The current demographic portrait of the Jewish people, distributed as it is between Israel and the Diaspora, is not new. Indeed, it is remarkably similar to the image reflected in sources dating back to the Talmudic period, starting in the third century ACE. Approximately 85% of the world’s Jews live in one of two population centers. One is the Land of Israel, the Jews’ sacred, historic home; the second is a prosperous, peaceful exile, then Babylon and today the United States of America.

The numbers in the contemporary demographic portrait are, of course, many times larger than the equivalent numbers in the Talmudic period. However, the percentages then and now are probably quite similar. There is also a notable resemblance in the political, economic, cultural and religious dynamics: supposedly, all the diasporas of the Jewish people, including the largest and strongest among them, have recognized the primacy of the center in the Land of Israel, sent donations, occasionally visited, supported it politically, and accepted its authority in certain matters. On the surface, both then and now, that has been the case. However, beneath this picture – at least in the Talmudic era – rages a hidden struggle for primacy, a struggle that gradually comes out into the open.

In late antiquity, the two great centers were home to a reciprocal and vigorous creative process that culminated in the works of Talmudic literature. Yet as the center in Babylon grew stronger and more established, the center in the Land of Israel suffered from the gradual erosion of its power, becoming weaker in comparison to the increasing strength of the Babylonian diaspora. Ultimately, sometime in the early Middle Ages, primacy finally and officially passed to Babylonian Jewry; the Babylonian Talmud, not the Jerusalem Talmud, became the most-learned text in the Jewish canon.

Is this history liable to repeat itself? We have no way of knowing, and history does not necessarily repeat itself. There can be no comparison between the strong, well-established Israel of our day and the Jews of the Land of Israel in the Talmudic period, who were partly subject to obstructive and hostile Byzantine Roman rule. Likewise, the spiritual-religious stability and continuity of American Jewry cannot yet be compared to that of Babylonian Jewry, which preserved its identity for many centuries. We may wish ourselves hundreds more years of Jewish presence in the Land of Israel, and hope that it may retain its centrality with respect to the Diaspora. In the meantime, we may learn something from the two Talmuds about the complexity of the relationship between two great Jewish centers.

*

In the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods, an intricate system of interplay existed between the communities in the Land of Israel and Babylon. A constant two-way interaction connected the two communities. This two-way interaction between the Babylonian exile and the Land of Israel entailed not only physical migration, but also additional dimensions: this was also a profound and complex spiritual movement. In the following, I wish to present a reading of a short story from the Babylonian Talmud, a story in which psychological and gender-related depths lurk beneath the ideological and halakhic surface. This story may help us to understand the complex nature of the competitive relations between the two centers of Jewish life in Israel and the United States.

The story, which appears in Tractate Kiddushin of the Babylonian Talmud, describes Rav Assi’s relationship with his elderly mother. Rav Assi, known in sources from the Land of Israel as “Rabbi Assi,” was one of the great third-generation amoraim (later sages) in the Land of Israel, and a friend and colleague of Rabbi Ammi. The two of them were known as “the esteemed priests of the Land of Israel” (B. Megillah 22a), and were dedicated students of Rabbi Yohanan, the greatest amora of the Land of Israel, who stood for many years at the head of the yeshiva in Tiberias throughout the third century. It turns out that Rav Assi fled to the Land of Israel in his youth as a result of his complicated relationship with his mother, and thus reached Rabbi Yohanan’s yeshiva in Tiberias:

Rav Assi had an old mother. She said to him, “I want jewelry,” and he made it for her. She said to him, “I want a man,” and he said, “I will try to find one for you.” She said to him, “I want a man as handsome as you.” He left her and went to Eretz Yisrael.

Rav Assi heard that she was coming after him. He came before Rabbi Yohanan and said to him, “What is the halakha with regard to leaving Eretz Yisrael to go outside of Eretz Yisrael?” Rabbi Yohanan said to him, “It is prohibited.” Rav Assi said, “If one is going to meet his mother, what is the halakha?” Rabbi Yohanan said to him, “I do not know.” Rav Assi waited a little while, and then came back to him. Rabbi Yohanan said to him, “Assi, you are determined to leave. May the Omnipresent return you in peace.”

Rav Assi came before Rabbi Elazar and said to him, “God forbid, perhaps he is angry?” Rabbi Elazar said to him, “What did he say to you?” Rav Assi said to him, “May the Omnipresent return you in peace.” Rabbi Elazar said to him, “If he was angry, he would not have blessed you.”

In the meantime, Rav Assi heard that her coffin was coming. He said, “Had I known, I would not have left.” (B. Kiddushin 31b)2

Rav Assi’s elderly mother comes to him with repeated demands of a clearly erotic character; the last, “a man as handsome as you,” exposes the subject of the mother’s forbidden desires. In response, Rav Assi flees to the Land of Israel. In this way, Rav Assi indeed fulfills the commandment of settling the Land of Israel. However, he does not fulfill this commandment for religious reasons – as Rabbi Yohanan and his fellows in the Land of Israel would surely have wanted – but for strictly personal reasons, as has been known to happen, and not just in the days of the amoraim of Babylon…

Soon after, he is alerted that his mother is coming after him. The story continues after Rav Assi has already arrived in Tiberias, and has heard that his mother is coming to the Land of Israel. We do not know how much time has passed, whether months or years. At any rate, over two-thirds of the story concerns Rav Assi’s deliberations as to whether or not to go out and meet his mother. Finally, he receives the news that his mother’s coffin is coming – that is, that she has already passed away. His response, which concludes the story, is: “Had I known, I would not have left.”

The story of Rav Assi has three partial parallels in the Jerusalem Talmud. According to one of them:

May a priest defile himself in honor of his father and mother? Rabbi Yasa heard that his mother had come to Bostra. He went and asked Rabbi Yohanan, may I leave? He said to him, if it is because of danger on the road, leave. If it is in order to honor father and mother, I do not know. Rabbi Samuel bar Rav Yitzhak said, Rabbi Yohanan still needs to answer. He importuned [Rabbi Yohanan], who said: If you have decided to go, return in peace. Rabbi Eleazar heard this and said: There is no greater permission than that. (Y. Berakhot 3:1, 23b; Y. Sheviit 6:1, 16b–17a; Y. Nazir 7:1, 34a)

In the parallels in the Jerusalem Talmud, the subject and the context is the restriction on leaving the Land of Israel, and the conflict has to do with whether the commandment to honor one’s mother justifies leaving the Land of Israel for “profane” land – a question lent additional force by Rav Assi’s priestly lineage. In these versions of the story, Rabbi Yohanan answers that if such a departure is necessary to ensure the safety of the mother, it is permitted, but if it is purely for the sake of honoring one’s mother, he does not know how to answer.

By contrast, in the version in the Babylonian Talmud, the commandment to honor one’s mother is not mentioned at all; Rav Assi’s motivation to go out and meet his mother is not necessarily honor. (It must be noted that the general context in the Babylonian Talmud pertains to the commandment to honor one’s parents, and from this point the Babylonian Talmud goes on to discuss the question of honoring one’s parents after their deaths. However, the subject is not mentioned at all in the dialogue or in the story as a whole.)

Rather, this version relates the opening passage of the story, which, unlike its parallels in the Jerusalem Talmud, describes the relationship between Rav Assi and his mother at relative length. From this opening passage, it turns out it was not the holiness of the Land of Israel that brought Rav Assi there, but shock at his mother’s behavior. Thus, in the Babylonian Talmud, the center of gravity in the story shifts from a halakhic comparison between the two commandments, as we saw in the Jerusalem Talmud, to a psychological depiction of mother-son relations.

The story deals with the relations between a son and his mother – a mother whose sexuality plays a dominant role in her requests to her son. These are impossible, perverted relations that cause her son to physically flee from her.3 The narrator then dwells at length on the relations between Rav Assi and Rabbi Yohanan, seemingly without cause. In doing so, the narrator sets up Rabbi Yohanan as a spiritual father to Rav Assi; Rav Assi is torn between his feelings for Rabbi Yohanan and his feelings for his mother. While the mother is portrayed as demanding, seductive, tainted by materialism and sexuality, the famous “father” is a great sage who understands Rav Assi deeply, accepts his distress, and permits his son-student to do as he wishes. In contrast to the sentimental, sexual Babylonian mother (characteristics symbolic of a foreign, even immodest culture) who repels her son, an intellectual, halakhic father is positioned in the Land of Israel, “the land of the fathers.” Rav Assi takes seriously this father’s responses and finds it difficult to leave him. Thus, an analogy of contrast is established between the biological mother in Babylon and the spiritual father in the Land of Israel.

Rav Assi’s concluding words, “Had I known, I would not have left,” have been interpreted by various commentators in two primary ways.4 The first interpretation maintains that Rav Assi had already gone out to meet his mother, and that he is sorry to have left the holy ground of the Land of Israel without cause, even for a moment.5 The second interpretation is that Rav Assi regrets having gone to the Land of Israel in the first place, rather than remaining in Babylon.6 Had he known that his mother would die so quickly, he would not have left. Perhaps he would have held out for a little longer had he known that her remaining days were few; perhaps he is sorry that he did not nurse her in the time before her death; perhaps he even thinks that his departure cut short her life.

According to the first interpretation, Rav Assi’s initial request was only to greet his mother and bring her back with him to the Land of Israel. However, an explanation of this kind assumes that the story is concerned with the question of whether honoring one’s parents justifies a temporary departure from the Land of Israel, as in the Jerusalem Talmud, and ignores the the relationship between Rav Assi and his mother, the central drama of the story in the Babylonian Talmud. Such a disregard for the heavy psychological weight of the story seems like an attempt to avoid the darkness at its heart. This explanation also assumes that the Land of Israel, which at first served Rav Assi only as shelter, has since taken on such a central religious significance for Rav Assi that he finds even the slightest departure difficult and is more upset about leaving than about the death of his mother. Thus, this first interpretation assumes a dramatic religious and philosophical transformation with regard to the Land of Israel – a transformation undergone by Rav Assi in the unspecified time between his departure from Babylon and his mother’s arrival in the Land of Israel.

Shulamit Valler has raised the possibility that Rav Assi wished to obstruct his mother’s arrival, and thought that going out to meet her would prevent her from settling beside him in the Land of Israel. According to this possibility, Rav Assi’s emotional detachment from his mother is so thorough and final that he wishes to distance her from himself at any cost. This possibility, too, sidesteps the grand drama faced by Rav Assi, although from another angle: by attributing to him total alienation from his mother and utter indifference to her difficult situation.

Rashi interprets Rabbi Yohanan’s answer as follows: “He reasoned that [Rav Assi] was resolved to return to his place in Babylon.” Rabbi Yohanan believes that Rav Assi wishes to determine whether he may return to Babylon, probably in order to live there with his mother. Rashi seems to attribute this understanding only to Rabbi Yohanan, but it is possible that this was also in fact Rav Assi’s intention. If so, we must understand Rav Assi’s concluding words, “Had I known, I would not have left,” as an expression of regret over having left Babylon at all. We may then understand Rabbi Yohanan’s final answer to Rav Assi, “Assi, you are determined to leave. May the Omnipresent return you in peace,” which highlights the matter of “return,” as Rabbi Yohanan giving his blessing for Rav Assi’s return to Babylon, despite the halakhic probibition, once he comes to understand the scope of Rav Assi’s distress. According to this more likely interpretation, Rav Assi regrets not that he has left Eretz Yisrael in order to meet his mother (once again, a conflict that is not mentioned at all in the story), but that he has left Babylon for the Land of Israel. He is saying: “Had I known before my departure from Babylon that she would soon die, I would not have left her.” Thus, in the final analysis, Rav Assi returns and chooses his Babylonian biological mother over his spiritual father in the Land of Israel.

Therefore, the story raises the need to choose between mother and father, and thus between Babylon and the Land of Israel. Babylon is the homeland identified with the mother, and it is difficult if not impossible to detach oneself from it. Even should he successfully remove himself physically, it seems that the hero remains emotionally connected, and he feels considerable guilt over his abandonment of her.

Rav Assi’s extensive deliberation, his flitting between sages, and his fixation on Rabbi Yohanan’s imagined anger likewise expose his fear of the need to choose between mother and father. They also reveal his ambivalence between a return to his mother in Babylon – a return decidedly regressive in nature – and the continuation of his flourishing life in the Land of Israel, “the land of the fathers.”

Thus, the story is open to two contradictory readings that both emphasize the conflict between mother and father, between Babylon and the Land of Israel, found at the heart of the story. Rav Assi’s final words, according to the interpretation set forth here, may also be read on two levels. On the national level, they explain why, despite the masculine spirituality of the Land of Israel, the Jews of the Babylonian exile find it difficult to go there, and most stay in the bosom of their Babylonian mother. On the personal-psychological level, they illustrate that the exit from the woman’s body does not conclude with birth, and that separation from the mother is accompanied by a complex and ongoing emotional process. This is, however, only one possible way of understanding the story, and most commentators chose to interpret otherwise.

According to the more common reading of the story, Rav Assi is entirely comfortable with his choice of Father-Israel, to the point that even a brief and temporary sojourn away from him and towards Mother-Babylon pains him. This interpretation suggests that the physical migration between Babylon and the Land of Israel has been completed, and reinforced by an emotional and religious migration. Rav Assi has firmly decided on Father-Israel.

In designing a story open to two contradictory readings, the Babylonian creators and redactors of the story expose, consciously or not, a deep truth. Rav Assi’s unresolved drama belongs not only to him – it is also the inheritance of the Babylonian sages, and perhaps also of American Jewry, and Diaspora Jewry in general, today.